Sommaire

- A holistic approach to contamination control

- Part 2: Turning constraints into opportunities to accelerate Sterility Assurance performance

- Key Elements of a Successful Cleaning and Disinfection Program

- Improving contamination control through risk analysis: a pillar of the CCS strategy according to ICH Q9 and Q10

- The control of surfaces in cleanrooms: Questions & Answers

- Methods to Validate Disinfectants

- Keys to the success of a GMP cleaning solution implementation project

- New to the world of disinfection?

- Drought decree: impacts & opportunities for the pharmaceutical industry

Zero CFU: a goal and an illusion. A holistic approach to contamination control.

When contamination is found in grade A, an investigation is launched, which is often a long and difficult process. Sometimes a probable cause is identified, but very rarely a definite root cause. Nevertheless, a CAPA is put in place and production operations can resume. Then, some time later, a new deviation is discovered.

Does this mean that the CAPA was ineffective or that the cause of the previous contamination was incorrect?

Whatever the answer, the production site or quality organization may face difficulties in their ability to conduct an effective investigation (“Root Cause Analysis”) or the identified CAPAs may not be effective (CAPA effectiveness check).

This article will attempt to shed new light on how to achieve lasting control of contamination.

1. The limits of environmental control

Historically, microbiological surveillance and environmental monitoring (EM) were considered to be effective ways of demonstrating good control of aseptic operations.

However, environmental monitoring provides only very limited information.

First, the ability of conventional methods (agar or liquid growth media for APS) to grow a potentially viable grade A microorganism is very low. Recovery rates are difficult to determine accurately because they depend on many factors (nature of the microorganism, viability, etc.), but we know that they are generally low, even very low.

Furthermore, samples are spatially limited. If a contact agar test is negative at a given location, this does not mean that the entire surface that the sample is supposed to represent is free of microorganisms. The same applies to air samples.

In addition, environmental controls are carried out at specific times. In Grade A, particle counts are continuous, but the same is not true for microbiological controls, which have a statistically very limited capacity to “capture” all events.

Given the low level of information provided by environmental monitoring, if contamination is found, how many other microorganisms are present?

Conversely, if no microorganisms are detected, how can we be sure that the area is sterile? These are the limitations of environmental controls, which can create the illusion that the area is free of contaminants. The absence of microorganisms in Grade A is indeed an expectation, but it is also an illusion.

The fisherman metaphor is well known. Just because a young fisherman doesn’t catch any fish doesn’t mean there are no fish in the pond. But the more fish there are in the pond, the higher the probability that the young fisherman will catch some.

Too often, the industry relies on these environmental controls to establish its contamination control strategy. This approach is no longer acceptable, particularly since the publication of the latest revision of Annex 1 of EudraLex in 2022.

Contamination control is actually based on a holistic approach that integrates the various elements needed to build a control strategy based on the design of barrier systems, bioburden reduction processes, and their implementation.

2. Protecting the “sanctuary”

The principles of aseptic production are conceptually very simple but at the same time very complex to implement.

The aim is to achieve zero microbiological contamination (0 CFU) and very low particulate contamination (< 100 particles of 0.5 microns per cubic foot) in the area where the product and containers are exposed: Grade A, which we call the “aseptic sanctuary.”

As in ancient Egypt, where the sanctuary of the pharaoh’s tomb was a forbidden room protected by a series of adjacent rooms with increasingly restricted access, Grade A is an area where human intervention is undesirable and which is protected by a series of clean rooms of increasing cleanliness.

The challenge is considerable: the bioburden outside the manufacturing plant is very high (millions of particles and microorganisms per square meter or cubic meter), inconsistent, and uncontrollable. This input factor requires progressive bioburden reduction processes that are robust and capable of reducing a wide spectrum of microorganisms from very high initial quantities.

3. The four elements of sanctuary protection

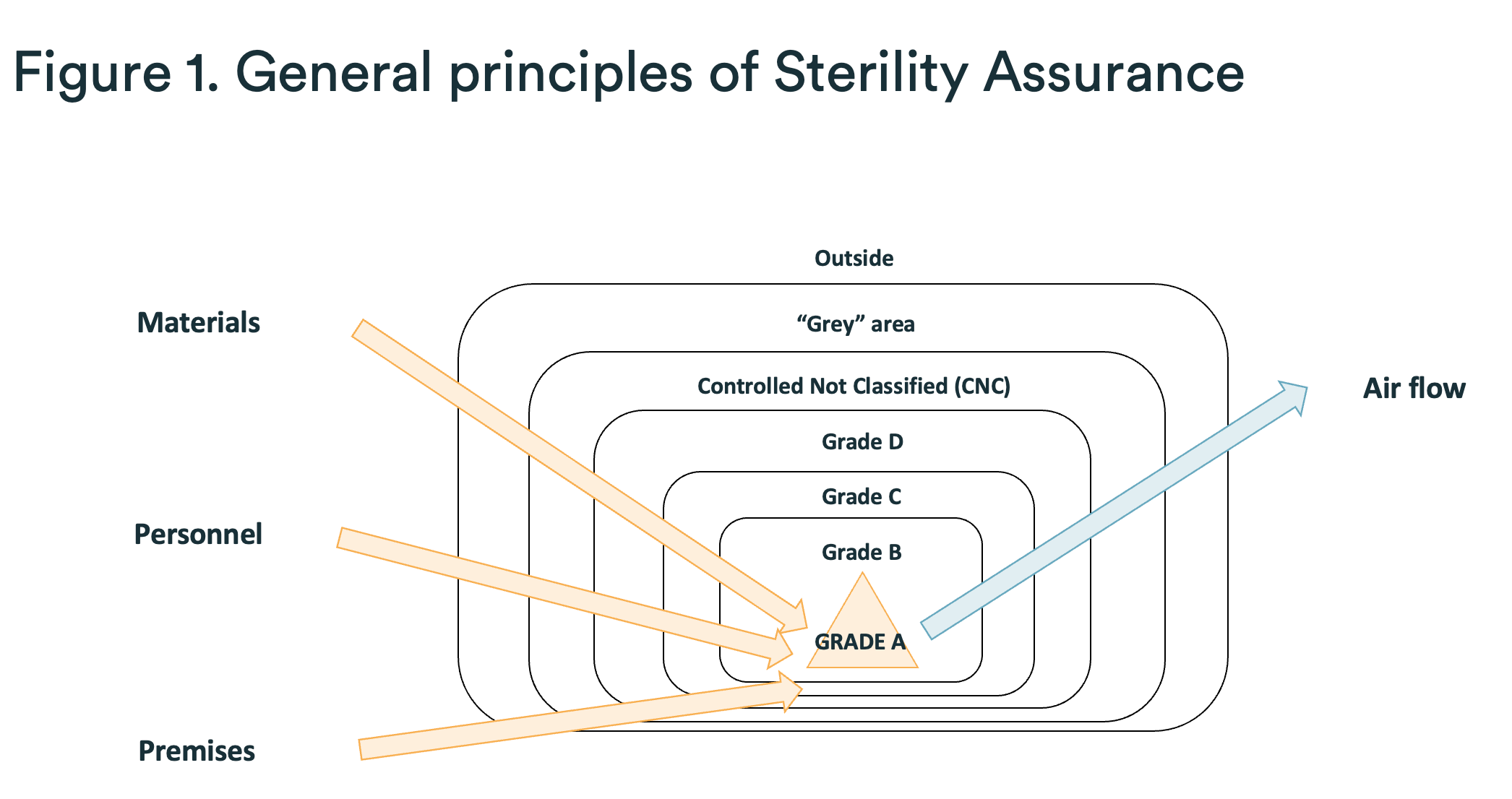

In order to protect the Grade A sanctuary from the “hostile” outside world (in terms of microbiological and particulate load), most sterile production sites feature different “layers” of protection, as shown in Figure 1.

Not all layers are always present. Two typical examples are as follows:

- The absence of a CNC zone in certain factories: in this case, the transition between the “gray” zone and Grade D must be given very special attention.

- The use of an isolator makes it possible to avoid use of a Grade B area: as a result, phases where the isolator is open (e.g., assembly) and where the Grade A sanctuary is therefore exposed to Grade C require additional precautions and protections.

We will now detail the various measures that must be taken in relation to four main elements (materials, personnel, premises, and airflow) in the manufacture of a sterile drug.

3.1 Materials

Bioburden reduction processes range from steam sterilization (one of the most robust processes) to manual disinfection (the most fragile process). The chemical and/or physical nature of disinfection or sterilization is an important factor, but so are the implementation aspects (automatic or manual). A holistic analysis of both elements (bioburden reduction system and implementation) should make it possible to establish the most appropriate strategy for the process and its design and to identify residual risks.

Bioburden reduction processes are generally carried out at the interface between two different levels of cleanliness in order to clean and reduce the bioburden on materials or equipment. This is done, for example, with autoclaves between Class C and Class B areas. This may also be the case for bio-decontamination with hydrogen peroxide between Class C and Class B.

There are practices involving bioburden reduction by disinfecting materialst in materials airlocks. If disinfection is done manually, it is subject to human variability, which is difficult to control and therefore difficult to validate. This poses a risk of contamination that is difficult to quantify. This is one of the main risks if the incoming microbiological load increases for various reasons, as discussed below.

It is also possible to have materials that are already sterilized and over-packaged so that they can be transported to cleaner classes by removing a layer of packaging when moving to a higher cleanliness class.

These bioburden reduction processes are critical and must be thoroughly analyzed to identify the risks and benefits associated with the various options available.

3.2 Personnel

If it is not possible to sterilize or disinfect, then the object must be “wrapped” to contain the contaminants.” This is what is done, for example, for personnel entering clean rooms.

Personnel arriving at the factory remove their street clothes and put on factory clothing. The purpose of this clothing is to limit contamination brought in by clothing that has been outside the factory. Many factories have a Controlled Not Classified (CNC) area that protects the D grade inside the factory. This is a first barrier where personnel add protection such as a cap, beard cover, gown, and shoe covers. From this CNC area, personnel enter through airlocks into areas classified as increasingly clean, and at each barrier (airlock between two classes), additional protection is worn to ultimately “wrap” the operator completely.

The latest revision of Annex 1 no longer allows personnel to enter the aseptic sanctuary (grade A) because the risk of contamination is too great. However, there are still many situations where the design of the facilities requires the presence of operators in grade A, particularly for freeze-dried products where partially closed vials must be transported from the filling line to the freeze dryers. Given that humans are the primary source of contamination, and even if everything is done to contain human germs as much as possible (clothing), this remains fragile. It is therefore almost “normal” to find a certain rate of positive results in Grade A if staff are working in these areas. We have encountered many situations of this type, and when contamination is found, an investigation is initiated even though the probability of finding a specific cause is low, as it is a cause common to the design of the facility.

Barrier technologies protect the product and, more generally, critical surfaces. Appendix 1 supports this approach and favors these barrier technologies. It is now prohibited to build new aseptic units using the old A in B aseptic zones.

While barrier technologies offer certain advantages and reduce the risk of contamination, there are specific risks that need to be analyzed. In particular, issues relating to the transfer of materials in an isolator must also be carefully studied. This is a potential route of contamination that has been little studied because barrier technologies, and isolators in particular, give a false sense of security. All the necessary precautions in the processes of reducing the bio-load of materials are applicable to barrier technologies like for conventional technologies.

3.3 Premises

Regardless of the bioburden reduction process, a barrier system is required between the outside of the factory and the aseptic sanctuary. These barriers must block contamination and allow the maintenance of an increasingly clean environment to ultimately achieve Grade A aseptic status.

Entrances and exits between two areas of different cleanliness levels are via airlocks for personnel on the one hand and for equipment on the other.

Airlocks allow the areas to be isolated from each other when the doors are opened. When a door is open on the “dirty” side, the door on the “clean” side must be closed. The airlock then becomes “dirty” and it takes a certain amount of time to return to the ‘clean’ level of cleanliness. This time is called “recovery time” and is well defined in ISO 14644 and Annex 1.

As we get closer to the Grade A sanctuary, the level of cleaning and disinfection of the rooms increases in frequency and intensity.

3.4 Air flows

Barriers are managed by air flows that “push” contaminants from the cleanest areas to the least clean areas. This is the principle of the air barrier and pressure cascades between different cleanliness classes. To ensure and maintain this air flow, there must be a minimum pressure difference of 10 Pascal between two particle classes. This flow also allows air to be evacuated to the least clean areas when the airlock doors are opened.

4. From case-by-case analysis to a truly holistic approach

We can see here that these simple concepts can be applied in many different ways. Each of these applications can give rise to new risks. As we have mentioned, one of the main risks is represented by manual interventions, as they are, by their very nature, dependent on humans. Reproducibility cannot therefore be demonstrated.

Once the main principles of bioburden reduction on the one hand and transfer from a clean area to a higher clean area on the other have been established, validation (EMPQ, APS) can take place. The results of EM microbiological monitoring then make it possible to verify that the implementation of the defined design produces the expected results, in particular zero contamination in grade A.

In the vast majority of cases, it is indeed an absence of contamination that is expected and observed. When a result is different from zero, there is most often an investigation into the location of the contamination and the time of contamination, as the first reaction is to search for the cause in space and time.

Given the complexity of the intimate processes involved in reducing the bio-load and transferring from class to class, it is more appropriate to look at the result in a broader environment. A positive result should be interpreted as a warning sign of a potential weakness in the system as a whole, not of the specific contamination itself.

The question should be: what could be malfunctioning in the system in place in terms of design and/or execution that is preventing sufficient protection of the Grade A sanctuary?

The signal sent by a result other than zero is not necessarily linked to an event that occurred within the factory premises.

For example, if the bio-load outside the plant increases significantly, the system in place may no longer be sufficient to contain this increase in bio-load. This is a typical situation if construction work is being carried out near the plant or the building, due to the increase in environmental germs that are often more resistant to conventional disinfectants. This is also the case, for example, in the fall with an increase in airborne fungal spores.

In reality, only a holistic view through a systemic analysis can reveal the flaws in the system. This is how the most likely causes of a grade A contamination can be found well upstream of the contamination site. The concept of Contamination Control Strategy (CCS) introduced by the latest revision of Annex 1 perfectly reflects this approach, as it encourages manufacturers to systematically implement a set of measures to protect the Grade A sanctuary.

Conclusion

This holistic view of contamination control relies on the men and women working at the production site. Whether it’s defining approaches and strategies or implementing them, it’s the men and women who make success possible. The best bioburden reduction processes and the best barriers between classes remain ineffective without competent and committed people.

It is through education and understanding the reasons behind the requirements that the principles of sterility assurance find concrete applications for contamination control. Each player must become the guardian of the sanctuary, and this attitude must be embedded in the culture of the site and the entire company.

Pharmaceutical companies that have integrated sterility assurance into their education program and culture have a definite competitive advantage because they are more immune to regulatory observations while increasing product quality and overall performance.

Antoine AKAR

Yves MOINARD