Summary

- Viewpoint of the ANSM’s Inspection Division (DI) concerning the ICH Q12 guideline

- ICH Q12: the basics. Review of the work of the A3P ICH Q12 GIC

- First steps towards ICH Q12: Leveraging process understanding & development data to define process Established Conditions

- ICHQ12 Implementation from an Industry Perspective with a Focus on Established Conditions

- ICH Q12 compliance and Unified Quality and Regulatory Information Management

- Burkholderia cepacia strikes again

- New EMA Sterilization guideline Guideline on the sterilisation of the medical product, active substance, excipient and primary container (EMA/CHMP/CVMP/QWP/850374/2015)

- How to store highly sensitive drugs? The benefit of functional coatings

Viewpoint of the ANSM’s Inspection Division (DI) concerning the ICH Q12 guideline

This article presents the viewpoint of the ANSM’s Inspection Division (DI) concerning the ICH Q12 guideline adopted very recently in Singapore at the latest ICH Assembly. It details the key elements in the guideline with an impact on good manufacturing practices (GMP), inspection and industry. It presents a few statistics within the scope of ICH Q12 and the communication requirements. Finally, it highlights the future challenges for its implementation.

1. A few words of introduction

ICH Q12 :

– concerns the famous “CMC” framework (chemistry / Chemistry-fabrication / Manufacturing – controls / Controls),

– describes the technical and regulatory considerations for pharmaceutical product lifecycle management,

– promotes “a harmonized approach which should benefit patients, industry and competent authorities by promoting innovation and continuous improvement in the pharmaceutical sector, by strengthening quality assurance and improving the supply of medicines ”,

– is consistent with prior ICH guidelines (Q8, Q9, Q10 and Q11),

– therefore primarily targets marketing authorization (MA) variations and assessors from the regulatory authorities responsible for granting these authorizations.

ICH Q12 indicates that :

– an effective pharmaceutical quality management system (QMS) as described in ICH Q10 and compliance with regional GMPs are necessary to take full advantage of this document. In particular, managing changes in the manufacturing chain is an essential element of an effective QMS,

– the roles of evaluation and inspection within the competent authorities are complementary in monitoring post-marketing authorization modifications,

– maintaining an effective PQS is the responsibility of a company (manufacturing sites and MAH where relevant),

– the objective is not to require a specific inspection assessing the state of the QMS before the industry can use the principles of ICH Q12,

– it is understood that a manufacturing site can be considered, in general, as complying with GMP while requiring preventive or corrective measures following an inspection, without necessarily using administrative suites of the injunction type,

– in the event that such shortcomings would affect the effectiveness of change management in the QMS, this could result in restrictions on the ability to use the flexibility provided for in ICH Q12,

– the responsibilities of the manufacturer and the MAH are clearly defined and concern:

• all the stakeholders in the manufacturing chain for a medicinal product, who must interact to effectively utilize knowledge and manage changes throughout the product lifecycle,

• They must manage the communication of information and the interactions of the QMS of these different stakeholders (internal and external to a company).

– in terms of communication, these responsibilities cover the following points:

• the modifications made to the “Established Conditions / EC” must be communicated quickly between the MA holder and the competent authorities, as well as between this holder and the entire production chain (and vice versa),

• the speed of communication is to be defined according to the impact of any change related to CE and must be targeted at the entities of the chain which must be informed of the change to implement it throughout the life cycle of the product concerned,

• the structure responsible for batch release should be informed of all relevant changes and where applicable, be involved in the decision making (role of the responsible pharmacist in France),

• the communication mechanisms regarding MAA changes and GMP issues should be defined in relevant documentation, including contracts with contract manufacturing organizations,

• A critical failure of a QMS at any point in the manufacturing chain can have an impact on the ability to use the benefits of ICH Q12. Therefore, managers should communicate these critical failures to the appropriate authorities concerned.

– the responsibilities of regulatory authorities focus on:

• communication between assessors and inspectors (nothing new in what is described),

• communication is encouraged between regulators across regions, in accordance with appropriate bilateral/multilateral arrangements. For example, to communicate about critical failures in the PQS of an aspect of the manufacturing chain that may impact the use of ICH Q12 in a product lifecycle.

Two key points were identified by the Inspection Division:

– the maturity of the PQS,

– communication between operators and regulatory authorities, between inspectors and assessors and between regulatory authorities.

What observations can be made in these two areas today?

2. A few GMP statistics in the field concerned by ICH Q12

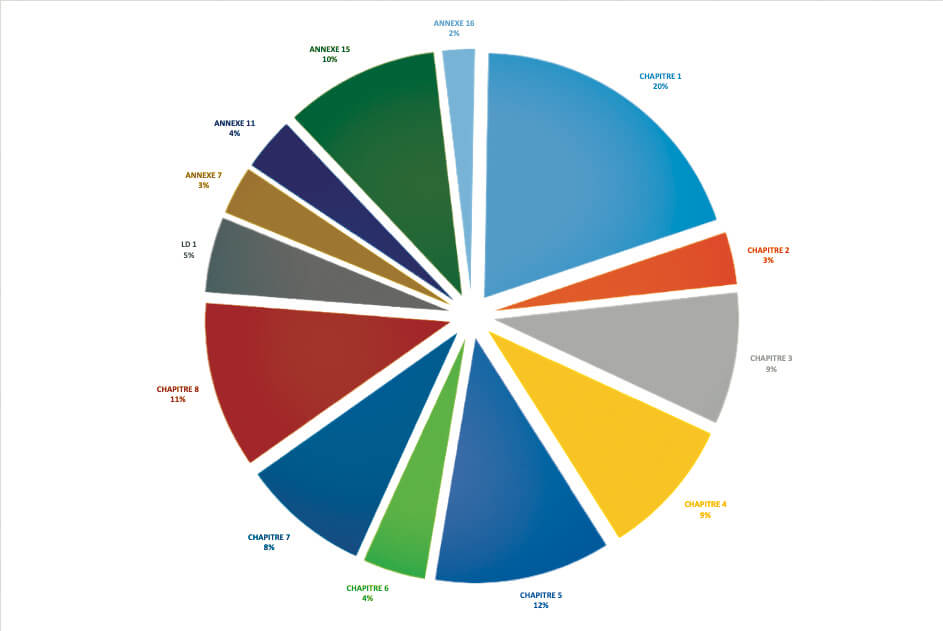

For the ANSM, in 2018 and in the field of medicinal products, it appears that 20% of critical or major deficiencies (850 identified during inspections) concerned Chapter 1 of GMP and therefore the PQS.(see graph above).

For the Irish agency (HPRA), when it came to major deficiencies, the PQS topped the list, recurring in 40% of inspections. The management of deviations was very frequently cited. This also topped the list for “other” deficiencies, with a level of close to 25%.

For the UK agency (MHRA) and out of 820 GMP inspections conducted between January 1, 2018 and September 10, 2019, there were 41 critical deficiencies and 676 major deficiencies identified with respect to the paragraphs specific to the PQS in chapter 1. If we refer to Annex 15 of the GMP guidelines (qualification and validation), the MHRA identified 43 major deficiencies in the field of change management alone.

Finally, for PIC/S, between 2011 and 2016, according to data gathered from around XNUMX regulatory authorities, deficiencies related to the PQS were those most frequently cited in inspection reports.

3. Communication between stakeholders

Communication channels do exist between regulatory authorities but there are currently none to manage the field of PQSs specifically. In the area of GMP, communication mechanisms exist:

– between operators and regulatory authorities for quality defects,

– between regulatory authorities (including inspectors and assessors), for quality defects and the management of GMP non-compliance. Although these are effective, they are limited to certain perimeters, such as the European Union (and access to its EudraGMDP database), the PIC/S or WHO for quality defects.

New systems therefore need to be envisaged for the management of the PQSs of sites located in countries such as the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and India, which are currently absent from GMP networks.

4. Conclusion

The text has just been adopted. This is therefore the start of the most complicated phase, i.e., the implementation of the guideline by all ICH stakeholders and, in particular, regulatory authorities.

What challenges will need to be faced and, in particular, what will the roll-out calendar be? Will it be coordinated to ensure optimal and harmonized utilization by industry?

The document should now indicate that regulatory authority members of ICH are asked to provide publicly available information, preferably on their website, about the implementation of ICH Q12 in their region, especially with regard to regulatory considerations,

– On a European level, what is the impact of this guideline on the regulation of variations? And on the funding of agencies whose budgets are linked to the submission of the corresponding applications ?

– Will it be necessary to modify the GMP guideline ?

– if the ICH text says that in case critical deviations from GMPs could affect the effectiveness of change management in the QMS, this could result in restrictions on the ability to use the flexibility provided by ICH Q12. Could this be extended to the fact that the changes which have occurred since the last inspection, confirming the proper functioning of the QMS, could be called into question (system analogous to what happens for good laboratory practices / GLP)?

– What training will be put in place with respect to ICH for regulatory authorities and industry? And on what terms ?

In Europe, what resources will be made available to qualified persons (for France: responsible pharmacists) to demonstrate the existence of a robust PQS throughout the manufacturing chain for a medicinal product ?

What new communication tools will be defined between industry and the competent authorities, and between these same authorities, throughout the manufacturing chain and lifecycle of a medicinal product ? These tools must include key players, such as the PRC and India. A structure including only regulatory authorities (IPRP) could lead a reflection process along these lines.

In fact, the real life of ICH Q12 is only just beginning.

Share article

Jacques Morénas – ANSM

Jacques Morénas has worked for more than 40 years in different structures of the ministry responsible for health and in particular in the direction of the inspection of the ANSM for 25 years. He is currently a technical advisor to the director of inspection. He participated in the drafting of ICH Q9, Q10 and Q12 documents. He is also a member of the executive committee of PIC / S as chairman of the training subcommittee.

Glossary

AMM : Authorization Market

ANSM : National Agency for the Safety of Medicines and Health Products (www.ansm.sante.fr),

HPRA : Health Products Regulatory Authority (www.hpra.ie)

ICH : International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (www.ich.org),

IPRP : International Pharmaceutical Regulators Programme ( www.iprp.global/home),

MHRA : Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Authority (www.gov.uk),

OMS : Organisation Mondiale de la Santé (www.who.int),

PIC/S : Pharmaceutical Inspection Cooperation Scheme (www.picscheme.org).