Sommaire

- Biofilms : Les bactéries résistent !

- Identification individuelle par séquençage d’une bactérie et d’une moisissure présentes en mélange

- Lyophilisation : comment utiliser la mesure manométrique de la température (MTM) pour comprendre l’influence de la température de nucléation sur la résistance au transfert de matière d’un produit

- L’activité des désinfectants sur les champignons communs de salles propres

- Cahier Pratique : Mise en place d’un système de biodécontamination sur une unité de biotechnologie

- Interview d’Alexandre Guerry, Project Manager R&D Cytosial Biomedic

- De nouveaux chemins dans la mesure Carbone Organique Total (COT ou TOC)

- Cytotoxic Chemical contamination risks and protective measures at hospital pharmacies

- Management – Rien n’est permanent sauf le changement, Partage d’expérience et de petits trucs…

Despite the implementation of collective protective measures, the exposure of hospital workers involved in the preparation and administration of cytotoxic drugs may still be referred to as an occupational health hazard. Many international studies have demonstrated that workers are being exposed despite the implementation of protective measures(1-6). To understand the problem, the risks need to be identified by considering the potential sources of contamination and the routes of exposure, and the weak points in the measures implemented for the protection of health workers need to be analysed.

Sources of contamination

There are two main sources of contamination: contamination generated during preparation process and contamination transferred by contact with contaminated surfaces.

The first main source of contamination is generated during the preparation process. Withdrawing, transferring and injecting cytotoxic solutions is related to the spread of contamination inside and outside the pharmacy(7). The use of filters during transfer should decrease the risk of aerosolisation. Nevertheless, some cytotoxics can pass through filters in vapour form(8-9), which can be correlated to the surface environmental contamination found in numerous studies(3-6, 10, 11) Some devices have been developed to ensure a close transfer from the vial to the final container. Those devices decrease the environmental contamination generated during the preparation process but cannot totally eliminate environmental contamination (12-14). The contamination generated during preparation is easily transferred to the gloves used and to the final product(15,16). This means that the surface of the final product is contaminated, which could contribute to the spread of contamination in other hospital departments, including wards.

The second main source of contamination is the surface contamination generated during the preparation process but also coming from the manufactured vials. Surface contamination generated during the process in hospital pharmacies is a multidrug chemical contamination since more than 30 different chemicals are simultaneously being handled. The cleaning and decontamination procedures used cannot be effective in removing and deactivating all of the chemical contaminants, which could contribute to the spread of contamination. Thus, handling of cytotoxic drugs, waste products and cleaning materials should not be carried out without protective clothing and methods to ensure the containment of cytotoxic drugs, and waste products should be implemented.

External surface contamination of manufactured vials was widely published for many years. International publications have shown that the outside surface of drug vials is contaminated with the corresponding drug(17-20) and even cross contaminated with other cytotoxics manufactured by the same company (21).This contamination is still an issue according to recent papers published (22-24). This type of contamination presents a risk of exposure for any worker in contact with the drug vials, not only during the preparation process but also when receiving the drug from the manufacturer and during storage. The handling of drug vials must be considered from the moment it is received to the time when it is discarded. Little attention has been paid to this risk, which explains why workers who are not directly involved in the preparation process can also be exposed(25). In addition, the hand disinfection procedure commonly used when handling drug vials outside of protective equipment (eg, biological safety cabinets [BSCs] or isolators) could be an additional exposure risk(26), which does not exist in organisations using automated disinfection procedures such as vapour-sterilised isolators. The main issue in terms of protection from drug vials contamination is the lack of consideration given to all of the tasks involving handling performed outside BSCs or isolators. Thus it is important to provide adequate protection to workers carrying out all of these tasks.

Routes of exposure

The main routes of exposure to be considered are the dermal and inhalation routes, with the dermal route being the main route of exposure(27). Protection by gloves is a major issue to be considered when handling cytotoxic drugs, and thickness, glove composition, nature of the drug handling and duration of use are factors influencing permeability and, thus, risk of exposure (28-32). Moreover a recent study(33) pointed out hand contamination of the personnel not directly involved in the preparation or administration of drugs possibly through transfer of contaminants from contaminated surface.

Protective/prevention measures

Surface contamination

External vials contamination

Manufacturers implemented corrective measures to reduce the external vial contamination. The methods implemented are cleaning procedure of vials and protective overwrapping (i.e shrink wrap and plastic containers). Cleaning procedure with washing machine is routinely used by pharmaceutical companies during manufacturing process(34). But it has been specified that this process is unable to remove potential contamination between flip off cap and rubber stopper giving a residual risk of contamination.

Considering the protective systems, shrink wrap was shown to considerably reduce the vial contamination(23), but it must be taken into mind that contamination under flip off cap is still an issue.

Main issue for operators’ exposure risk is the handling procedures of vials outside collective equipments. A study presented in 2009 by Mosset et al.(35), simulating the procedure for introducing vials into BSC pointed out the risk of using spraying method with disinfectants and suggested the substitution of spraying by wiping method to limit the spread of contamination. In a similar way(36), Mason et al., 2005 pointed out the risk of dermal exposure outside isolators when spraying vials outside isolators. To limit exposure of operators with contaminated vials, proper gloving procedure is a simple personal protective measure but must be properly implemented.

End product contamination

When considering the residual contamination of vials in combination with the process of preparation, contamination can be transferred to the final products as previously shown by Gilles et al, 2004(37). In similar way as the manufactured vials, the final product is also chemically contaminated and probably cross contaminated by more than one cytotoxic inside the collective equipment. Proper gloving, with high frequency of changes is able to limit this contamination. Kamguia et al.(38), reduced the contamination of final product by implementing additional cleaning method using anionic surfactant agent. More recently, Queruau Lamerie et al (39), highlighted the interest of surfactant agents for removing cytotoxic contamination on surfaces. So, more than an universal method for degradation of cytotoxic which is not available, it is worth to use a cleaning method able to remove the contaminants from surfaces (i.e. surfactant) in combination with proper methods for containment and destruction of waste.

Collective protective equipment

Two main systems are used for general collective protection of operators: Bio Safety Cabinets (BSCs) and isolators.

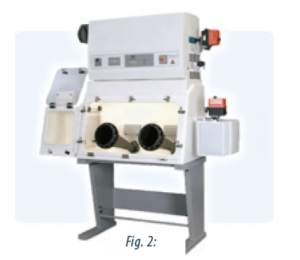

BSCs are vertical unidirectional airflow working cabinet. BSCs specially designed for hazardous drug preparation are BSCs II (fig1) and BSCs III (fig2).

BSCs blowing the air back into the room (BSC IIA) should not be used. The system used should be at least a class IIB cabinet (40), which means that the exhaust air is vented to the outside of the building. A class IIB2 (total exhaust; non-recirculation) cabinet should preferably be implemented because window and attached gloves through the windows for handling (fig2).

When using BSC II the contamination generated during the preparation process may be spread by aerosolisation and by the workers themselves. Considering the risk of contamination spreading through the worker’s hands and due to the lack of physical barrier, special attention must be paid to the gloves and gowning material worn in BSCs.

BSC III provides the physical barrier during compounding drugs, but special attention must be paid to cleaning operations when opening front windows where surface contamination may be transferred to the operators and background environments.

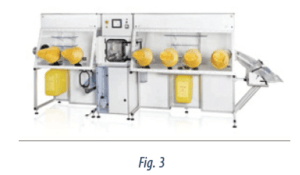

Isolators are sterile, enclosed areas(41,42) that allow physical protection for workers during the preparation process and ensure the containment of the hazardous products generated during this process. To ensure the containment of hazardous products, the exhaust air is vented to the outside of the building. In addition, attention should be paid to the tasks performed outside the isolator, such as the handling of vials, end-products and waste. In the case of the latter two, containment devices directly attached to the isolator wall should be used, thus ensuring the wrapping of the final product or waste without any breach in sterility and containment (see Figure 3). Good enclosure maintenance, including routine checks (eg, leaks in the wall, integrity of manipulation devices [attached gloves and sleeves]), is key in the use of isolator technology.

The main difference between BSC is the permanent physical barrier provided by the isolator technology, which explains the low level of environmental contamination(15,26) found next to isolators, compared with BSCs.

Personal Protective equipment

Gloves: Attention should also be given to the choice of glove and the duration of use. Double gloving and changing gloves at least every 30 minutes are the minimal requirements, according to both the NIOSH (43) and ASHP guidelines(40). Some authors have suggested that changing gloves more often may be related to lower levels of surface contamination. Attention must be paid to alcohol use, which may facilitate permeation of drugs through the gloves. However, one recent study(44) assessing the risk of permeation through gloves with simulated method when alcohol treatment was used, showed low risk of permeation.

Mask: To reduce inhalation risks, protective masks (FFP respirators) must be worn in tasks at risk of exposure such as handling of vials, treatment of vials before entering the BSC or the isolator and spill management. Surgical masks must not be used for this purpose because they are not intended to protect operators from air contamination.

Clothing: Proper gowning must not be neglected as permeation can occur (3) and could be an unexpected source of exposure. NIOSH (2004)(43) suggested the use of disposable coated gowns to prevent permeation.

Conclusions

Safe handling of cytotoxic drugs means that the whole process needs to be considered, from delivery of the drug to the hospital pharmacy through to administration to the patient. Regarding the problem of drug vial contamination, some authors suggest that manufacturers should improve cleaning deactivation procedures(45) and should provide the drugs in special containers to guaranty containment and sterility, thus allowing the user to put the vials directly inside the BSC or the isolator and removing the risk generated by outside handling.

Regarding the problems of contamination associated with the preparation process, methods ensuring chemical containment inside the BSC or the isolator should be implemented. This includes transfer devices that can reduce surface contamination during the preparation process. The highest level of containment would be offered by a physical barrier, which implies that endproducts, waste and cleaning materials need to be evacuated through disposable transfer containers. Personal protective equipment should be used for the handling of cytotoxics in wards. In this case, the patient is the major source of contamination and, in addition to the use of personal protective clothing, containment measures regarding the hanhandling of the patients’ excretas and the use of negative-pressure ventilation systems in the patients’ rooms should be implemented. The handling of cytotoxics in the pharmacy and in the wards requires highly trained staff working according to a quality assurance programme that should include written policies on chemical contamination risk. Surface contamination and biological monitoring are valuable methods to identify unexpected risks and to implement corrective measures.

Sylvie CRAUSTE-MANCIET – MCU-PH, PhD, PharmD GERPAC

crauste-manciet.sylvie@wanadoo.fr

Partager l’article

Références

1. Ensslin AS, Pethran A, Schierl R, Fruhmann G. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 1994;65:339-42.

2. Ensslin AS, Stoll Y, Pethran A, et al. Occup Environ Med 1994;51:229-33.

3. Minoia C, Turci R, Sottani C,et al. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 1998;12:1485-93.

4. Sessink PJ, Anzion RB,van den Broek PH, Bos RP.Pharm Weekbl [Sci] 1992;14:16-22.

5. Sessink PJ, Boer KA, Scheefhals AP, et al. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 1992;64:105-12.

6. Sessink PJ, Friemel NN, Anzion RB, Bos RP. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 1994;65:401-3.

7. Spivey S, Connor TH.Hosp Pharm 2003;38:135-9.

8. Kiffmeyer TK, Kube C, Opiolka S, et al. Pharm J 2002;268:331-7.

9. Connor TH, Shults M, Fraser MP. Mut Res 2000;470:85-92.

10. Connor TH, Anderson RW,Sessink PJ, et al. Am J Health-Syst Pharm 1999;56;1427-32.

11. Micoli G, Turci R, Arpellini M, Minoia C. J Chromatogr B 2001;750:25-32.

12. Connor TH, Anderson RW, Sessink PJ, Spivey S. Am J Health-Syst Pharm 2002;59:68-72.

13. Sessink PJM, Rolf MAE, Ryd�n NS. Hosp Pharm 1999;34:1311-7.

14. Vandenbroucke J, Robays H.J Oncol Pharm Practice 2001;6:146-52.

15. Crauste-Manciet S, Sessink PJ, Ferrari S, et al. Ann Occup Hyg 2005;49:619-28.

16. Favier B, Gilles L, Latour JF, et al.J Oncol Pharm Practice 2005;11:1-5.

17. Delporte JP, Chenoix P, Hubert P. Eur Hosp Pham 1999;5:119-21.

18. Favier B, Giles L, Ardiet C,Latour JF. J Oncol Pharm Practice 2003;9:15-20.

19. Mason HJ, Morton J, Garfitt SJ,et al. Ann Occup Hyg 2003;47:681-5.

20. Nygren O, Gustavson B,Strom L, Frieberg A. Ann Occup Hyg 2003;46:555-7.

21. Fleury-Souverain, S., Nussbaumer, S., Mattiuzzo M et al. J Oncol Pharm Pract 2014 ;20 :100-111.

22. Touzin et al., Ann Occup Hyg.2008 ;5:765-771

23. Schierl et al., Am J Health-Sys Pharm ; 2010 ;67:428-429

24. Hama et al., 2011 ; JOPP ; 18 :201-206

25. Schreiber C, Radon K, Pethran A, et al. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2003;76:11-6.

26. Mason HJ, Blair S, Sams C, et al. Ann Occup Hyg 2005;49:603-10.

27. Fransman W, Vermeulen R, Kromhout H. Ann Occup Hyg 2004;48: 237-44.

28. Slevin ML, Ang LM, Johnston A, Turner P. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 1984;12:151-3.

29. Stoikes ME, Carlson JD, Farris FF,Walker PR. Am J Hosp Pharm 1987;44:1341-6.

30. Connor TH. Am J Health-Syst Pharm 1999;56: 2450-3.

31. Klein M, Lambov N, Samev N, Carsten G. Am J Heath-Syst Pharm 2003;60:1006-11.

32. Wallemacq PE, Capron A,Vanbinst R, et al. Am J Health-Syst Pharm 2006;63:547-55.

33. Hon C-Y, Teschke K, Demers PA et al. Ann Occup Hyg, 2014, 58 :761-770.

34. Pharmaceutical companies (debate). 12th GERPAC Conference, Hyères, October 2009

35. Mosset et al., 12th GERPAC Conference, Hyères, October 2009

36. Mason HJ, et al. Ann Occup Hyg. 2003 ;47:681-685.

37. Gilles et al., Arch Mal Prof 2004 ;65:9-17

38. Kamguia et al., 8th GERPAC Conference, Hyères, October 2005American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Am J Health-Syst Pharm 2006;63:1172-93.

39. Queruau Lamerie et al, 14th GERPAC Conference, Hyères, October 2011

40. American society of Health-System Pharmacists. Am J Health-Sys Pharm 2006;63:1172-93

41. Agalloco JP, Akers JE. Technical report N°34. PDA J Pharm Sci Technol 2001;55 Suppl TR34:1-23.

42. Cazin JL, Gosselin P.Pharm World Sci 1999;21:177-83.

43. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Preventing occupational exposure to antineoplastic and other hazardous drugs in health care settings. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2004 �165/

44. Capron, A., Destree, J., Jacobs, P. et al., Am J Health-Sys Pharm 2012;69:1665-1670

45. Connor TH, Sessink PJ,Harrison BR, et al. Am J Health-Syst Pharm 2005;62:475-84.