Summary

- There is everything to gain from working in campaign mode, a breakthrough in isolator productivity

- Visual inspection: main findings of ANSM inspections

- Cleaning validation of production equipment: Visual inspection, accreditation of staff in “visually clean”

- A Refresher on Disinfectant Wet Contact Time

- THE EU MDR and IVDR : Combination products now subject to the same degree of surveillance as standalone medical devices

- Suitability of the Mono-Mac-6 cell line for the detection of endotoxins and non-endotoxin pyrogens

- Biological indicators, random growth. Is your decontamination cycle really at fault?

- Determining a Strategy for Container Closure Integrity Testing of Sterile Injectable Products

- Efficient Control Strategy enabled by structured Knowledge

- High-performance solution for real-time colony counts on filtration membranes in microbiological analysis with ScanStation

Visual inspection: main findings of ANSM inspections

The presence of visible particles in parenteral preparations has long been and remains a subject of major concern for manufacturers and health authorities. Indeed, the presence of visible particles in a parenteral preparation can call its safety into question(1).

Consequently, it is expected that the presence of visible particles is reduced as much as possible in all parenteral preparations.

The recent development of normative and regulatory texts shows the current interest in reinforcing the visual inspection or “candling” of injectable medicines, which is a fundamental step in protecting their production (1,4,5).

There are significant numbers of batch recalls in France because of the presence of particles in parenteral preparations. In 2016, for example, this was the cause of 10% of all batch recalls of parenteral preparations, and of 17% in 2017 and 20% in 2018.

tHE ansm has conducted a study to evaluate the current status of visual inspection practices on the sites of manufacturers of parenteral preparations or Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMP) for which it carries out inspections in accordance with Annex 1 of Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP)(2) or Good Manufacturing Practices for Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (GMP-ATMP) as appropriate(3).

1. Methodology of the study

The study consisted in carrying out a review of all inspection reports on pharmaceutical establishments manufacturing parenteral preparations for the period January 2016 to June 2019 so as to obtain data on the deviations noted in inspections. Sites that manufacture chemical medicines were distinguished from sites that manufacture biological medicines (60 sites manufacturing biological medicines and 44 sites manufacturing chemical medicines) in order to look for any features specific to the area in question. All deviations noted in inspection reports (critical, major and other) were included and any administrative consequences were studied in the event that critical or major deviations had been noted.

The establishments concerned by the study carried out were located both in France (90%) and abroad (10%) within the framework of inspections carried out on behalf of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) or in support of the World Health Organisation (WHO). Great diversity was observed amongst establishments manufacturing biological medicines, such as manufacturers of ATMPs, vaccines, establishments carrying out plasma fractionation, and included private and public organisations.

With the aim of analysing the results obtained and of identifying the problems most frequently encountered in the various inspection reports, eight subcategories were defined (1. Processes, 2. Documentation, 3. Trends analysis, 4. Accreditation of staff, 5. Visual inspection environment (conditions), 6. Defects and defect library, 7. Acceptable quality level (AQL), 8. Qualification/validation of automated machinery). It is however important to emphasise that the same deviation may have been attached to several subcategories, when different problems were reported in these subcategories. In addition, deviation criticality was also studied so as to define the subcategories that generated the most critical deviations in inspections.

Over the period studied, 161 GMP inspections were carried out, involving 104 different establishments, some establishments having been the subject of repeat inspections.

The following binding references in force at the time of the study were used to look for deviations noted in association with visual inspection: GMP Guideline 1 item 124, the European Pharmacopoeia 2.9.20, GMP-ATMP 9.85 and GMP-ATMP 2.42. However, it should be emphasised that the GMP-ATMP guidelines have been applicable since May 2019 and few deviations were noted in relation to this regulatory reference at the time of the study.

2. Result of the study

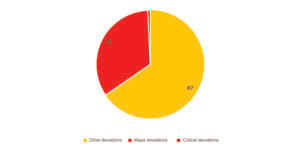

133 deviations were noted in association with visual inspection in 75 inspections, that is an approximate average of 2 deviations per inspection. In total, 51 of the 104 establishments inspected had deviations relating to visual inspection, that is almost half of the sites inspected. The distribution of deviations according to criticality was as follows: 87 other deviations, 45 major deviations and 1 critical deviation (Figure 1).

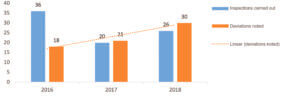

The trend in the number of deviations per full year between 2016 to 2018 on sites manufacturing biological medicines (Figure 2) showed an increase which was not correlated with the number of inspections carried out. It was the same for sites manufacturing chemical medicines where a marked increase was also observed and which was not correlated with the number of inspections carried out.

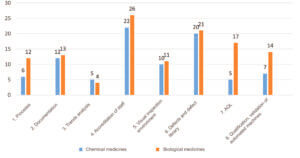

The breakdown of deviations by subcategory (Figure 3) showed that subcategories 4 “accreditation of staff” and 6 “defects / defect library” clearly emerged as the predominant problem areas noted during GMP inspections. The breakdown of deviations by criticality revealed that subcategories 1 “Processes” and 5 “visual inspection environment (conditions)”, displayed a high proportion of major deviations followed by subcategory 3 “trends analysis”.

The breakdown of deviations by subcategory in accordance with site type (chemical or biological) was slightly different (Figure 4). Sites manufacturing biological medicines had a larger number of deviations related to processes, AQL and qualification /validation of automated machines.

This difference can be explained in large part by a higher level of automation of visual inspection on sites manufacturing biological medicines in comparison with sites manufacturing chemical medicines.

The administrative consequences (batch recall, letter in advance of injunction and injunction) associated with the different major and critical deviations noted during the period studied were also investigated. Of the 75 inspections for which at least one deviation had been noted in relation to visual inspection, 23% resulted in administrative consequences and in half of the cases this involved letters of injunction. It should be emphasised that the corrective actions associated with visual inspection may go on for a long time (from 9 to 12 months) as they very often require a profound reassessment of visual inspection processes when methodological fundamentals require modification.

3. Discussion

Subcategory 1 “Processes” contains all the deviations associated with the fundamentals of visual inspection and reflecting the global visual inspection strategy adopted by the site in question. Visual inspection rejects which are inspected again without justification and changes in the levels of false rejects during visual inspection that are not controlled represent the deviations most commonly found in this subcategory.

The re-inspection of rejects from a first visual inspection could not occur without justification of the suitability of these rejects (4). The presence of bubbles or other artefacts in the products commonly claimed as being the origin of potential re-inspection operations, must be demonstrated for each product inspected visually. A level of false rejects that changes over time must be considered a quality criterion as it may also represent a warning sign of a non-viable configuration of the visual inspection process and of a settings problem, even of an qualification problem related to the visual inspection equipment.

Subcategory 2 “Documentation” contains all the deviations associated mainly with deviations relative to the traceability of visual inspection operations. Consequently, this subcategory is not specific to visual inspection and no further comment will be made about this group in the context of this study.

Subcategory 3 “Trends analysis” contains all the deviations associated with monitoring changes in the defects noted for each of the products studied. These trend analyses are expected by product type, as the grouping together of several different products in the same trends analysis is not appropriate without solidly established justification.

As the objective of these trend analyses is to provide warning sufficiently in advance of any aberration of the inspection system in place(5), the establishment of warning and action thresholds for the different categories of defect by product are expected so as to put in place the corrective and preventive actions necessary before the action threshold is exceeded. If warning and action limits are exceeded, an investigation into the most likely causes must be conducted and the necessary corrective actions must be deployed before resuming visual inspection operations.

Subcategory 4 “Accreditation of staff” was the subcategory that displayed the largest number of deviations in this study. The main problem noted was associated with a visual inspection speed which was applied during production but for which there was little or nothing in the production operator qualification process to justify its use.

In addition, very often qualification conditions did not take account of conditions of operator “fatigue” at the end of the shift (5) or defined break times which must also be justified. The other problem noted was associated with operator accreditation conditions, where the acceptance criteria were not established or were insufficiently established: for example, the number of non-compliant units to be detected among compliant units, the percentage detection of critical and major deviations during accreditation and the number of initial and periodic qualification runs.

Subcategory 5 “Visual inspection environment (conditions)” contains the deviations associated with visual inspection parameters which are not defined or are insufficiently defined during production. This involves, for example, acceptance testing parameters for semiautomatic visual inspection equipment which are not fixed during production, the absence of verification of the transfer speed of units inspected visually that could impact the reproducibility of visual inspection operations, and the rotation parameters of the units to be inspected which are determined in qualification but not fixed in routine production. Optimal lighting conditions and the verification (particularly metrological) of lighting parameters on a regular basis also represent some of the deviations regularly noted in this subcategory.

Subcategory 6 “Defects and defect library“, displays the second-highest number of deviations noted in this study, after accreditation of staff. Generally, the defects to be looked for during visual inspection in a given product are defects that have been recognised for this product (during product development and collected during routine production) meeting the definition “after filling, products for parenteral use must undergo an individual inspection intended to detect all foreign bodies or any other defect” as specified in the GMP (2,5). Defects such as opalescence, colouration, turbidity or the presence of precipitate commonly listed in critical defects and which must be looked for in the context of staff accreditation and qualification of semiautomatic and automatic visual inspection equipment as the case may be, are not always effectively investigated by automatic visual inspection, while the same defects are easily detected by manual inspection. Regarding defect libraries, the defects in them are not always preferentially collected from production but are predominantly created, which can introduce bias during accreditation of production operators and qualification of visual inspection equipment. It is commonly accepted that some defects cannot be collected from production, because of their rarity for example, and they must be subject to justification. In the event that defects are created, the methods for creating them and their composition must be defined, as well as the methods for their maintenance over time.

Subcategory 7 “AQL (Acceptable Quality Level)” represents deviations associated with an additional test (after the individual inspection of each container) often performed in accordance with a sampling plan based on a sample number and an acceptance value derived from the tables defined in the ISO2859-1 standard or by another statistical method(1). It is essential to define the AQL limits for each category of defect and in the event that AQL limits are exceeded, an investigation must be opened. The number of samples taken into account in calculating the AQL are must also be based on the quantity of units actually produced.

In the event of a repeat visual inspection after opening an investigation, it is expected that a test with a stricter AQL (level III for example) is carried out by an operator who did not take part in the initial batch inspection, so as to ensure that the performance of the stricter test is independent of the initial test.

Finally, subcategory 8, “Qualification and validation of automated machines” comprises the qualification of automated and semi-automated machines, as well as the validation of visual inspection processes. Semi-automated and fully-automated visual inspection can be performed subject to validation in relation to manual inspection, which remains the reference for visual inspection (5). Consequently the transition from manual visual inspection to semi-automated or automated processes, particularly by comparing the results obtained during automated visual inspection with manual inspection (“Knapp test”), must be handled with great care. For example, for particulate defects, it will be important to define the threshold for the size of particle detectable by production operators in accordance with verifiable data and which will serve as a baseline for the qualification of automated equipment. The deviations most commonly encountered in this subcategory involve the detection capacities of automatic visual inspection which are not at least equal to manual visual inspection, comparison tests between manual visual inspection and automated visual inspection which do not include all types of defect encountered in production or a rationale for the inclusion of defects which is not explained, or finally, a level of false rejects in the performance qualification of semi-automated or automated equipment which is not controlled (1). It should be emphasised that the deviations noted in this subcategory very often require basic corrective actions that may take several months as they very often require a review of all visual inspection processes.

Conclusion

As we have seen, a significant percentage of deviations noted during GMP inspections are associated with visual inspection. Despite technological advances in the detection of defects and the automation of visual inspection operations, the fundamentals of visual inspection must not be neglected for all that. The recent development of normative and regulatory texts should greatly improve the understanding of the expectations of health authorities as regards visual inspection.

Routine observation of manual and automated visual inspection operations should lead to a number of essential questions, such as:

- Does 100% individual inspection allow the detection of all foreign bodies and all defects? (for the defects known by the manufacturer); is manual visual inspection always the reference used for semi-automatic and automatic visual inspection operations; and more particularly for previously qualified equipment?

- Are staff training and accreditation carried out using the speeds established in qualification and applied in production?

- Have all defects been collected as far as possible from production, and if not, is there justification for the creation of defects?

- Are the management of defect libraries and the creation of defects, where appropriate, subject to detailed and applicable procedures? What about their maintenance over time?

- Is the comparison (Knapp test or equivalent) between manual and automatic visual inspection robust? Are the results consistent? Are the defects incorporated in the Knapp test subject to justification and on what on which basis?

- Are annual operator re-accreditation and periodic re-qualification of equipment provided for and on which basis?

Finally, it is important to emphasise that in this study, we focused mainly on methods of detection of defects already existing in production. It is important to recall that preventing the appearance of defects is of great importance, that visual inspection is a complete process which must take account of each production step (raw materials, packaging items, production conditions, e.g.) that is liable to generate particles, and that methods to prevent such generation must be put in place.

Partager l’article

ANSM

Références

[1] European Pharmacopoiea, Recommendations on testing of particulate contamination: visible particles (5.17.2.) (Draft for consultation) 2019

[2] EMA, Eudralex volume 4 Annex 1 2008

[3] EMA, Eudralex volume 4 Part 4 GMP Requirements for Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products

[4] USP (1790) Visual Inspection of injections 2017

[5] EMA, Eudralex volume 4 Annex 1 (Draft for consultation) 2020

[6] Julius Z. Knapp and Harold K. Kushner, Generalized Methodology for Evaluation of Parenteral Inspection Procedures, Journal of Parenteral Drug Association, January-February, 1980, Vol 34, No 1.